General History of Africa: An Incredible Scientific and Intellectual Journey

- Ali MOUSSA IYE

- Nov 16, 2025

- 5 min read

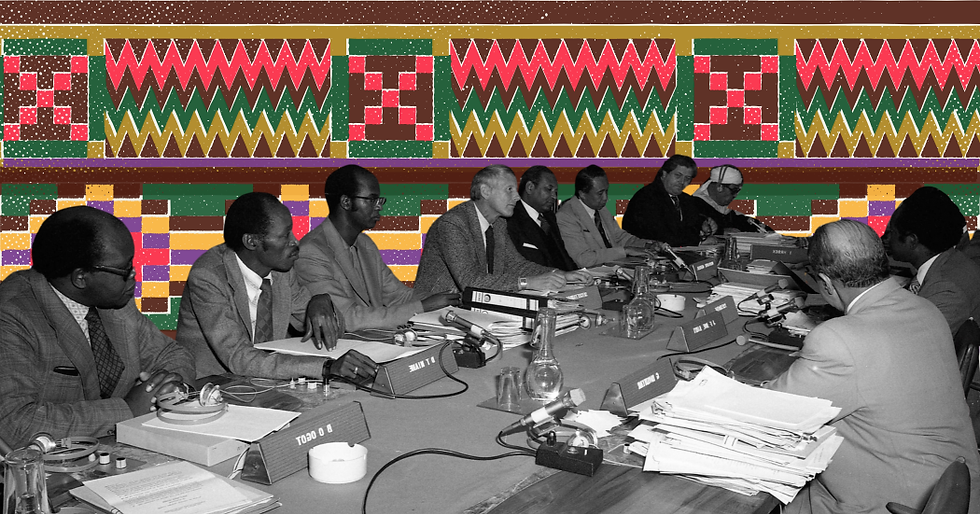

It cannot be emphasized enough how the General History of Africa (GHA) has been and remains an unprecedented academic as well as political undertaking. From the outset, it aimed to provide a response to the aspirations of African peoples to reclaim the narrative of their history and build solidarity based on their historical unity and shared heritage with African diasporas. The Pan-African orientation of the project was clearly stated in the presentation of all the volumes by the Chair of the first International Scientific Committee, Behtwell Allan Ogot. The project was launched in 1964, just one year after the creation of the Organization of African Unity (OAU), the body tasked with promoting the emancipation and unification of the continent.

Despite numerous attempts to discredit and sabotage the endeavour, the GHA successfully mobilized over 350 specialists during its first phase. Over 35 years, they produced a colossal body of knowledge on the ingenuity of African peoples and their cultural, scientific, social, and political development spanning more than three million years. The project sparked lively and passionate debates on essential questions: the historicity of African societies, the diversity of historical sources, the African origins of Egyptian civilization, and African contributions to humanity.

Some of the greatest African historians and thinkers of the 20th century participated in this venture, including Cheikh Anta Diop (Senegal), Adu Boahen (Ghana), J. F. Ade Ajayi (Nigeria), Joseph Ki-Zerbo (Burkina Faso), Hampaté Bâ (Mali), Ali Mazrui (Kenya), Gamal Mokhtar (Egypt), and Mohamed el Fasi (Morocco). They engaged in intellectual exchanges with peers from other regions of the world, profoundly transforming academic discourse on Africa, its peoples, and its diasporas.

Completed in 1999, the first phase of the project resulted in a monumental eight-volume collection. These volumes were published in main editions, abridged editions, and translated into thirteen languages, including three African languages (Hausa, Kiswahili, and Fulfulde). This phase also produced thirteen guides on African historical sources and twelve complementary publications, Studies and Documents, on debated topics.

Contributors to the first phase faced three types of challenges:

Political challenge: They rigorously responded to the recurring call of African and Afro-descendant intellectuals and enlightened political leaders to support Africa’s liberation process by reshaping minds through the reconstruction of African history freed from colonial perspectives. Considering the number of prejudices scientifically deconstructed, the GHA successfully rose to this challenge.

Methodological challenge: It was necessary to invent new ways of understanding African historical realities and to design appropriate methods and methodologies. By rehabilitating oral sources, documents in African languages transcribed in Arabic (Ajami), and other sources of knowledge such as arts, music, and even natural sciences, the GHA innovated and met this challenge.

Epistemological challenge: The GHA sought to revisit paradigms, concepts, categorizations, and notions applied to Africa and to shed light on the conditions of knowledge production about Africa. For example, it began exploring African toponyms, ethnonyms, and anthroponyms to introduce African designations. Due to the deep internalization of colonial terminology, this work remains incomplete, though it laid a path forward.

Produced with a pluralistic approach involving top African and international experts in African history, the GHA helped re-establish key facts:

Africa has not only a history but the longest history in the world, spanning over three million years, and played a leading role for the first 15,000 centuries of human history.

The earliest civilizations, including ancient Egypt, originated from and were inspired by African peoples.

The Sahara was never a barrier between a so-called Sub-Saharan Africa and North Africa but rather a space of contact and dynamic exchange among African peoples.

Africa was never cut off from the rest of the world and has always been in contact with Asia, the Middle East, Europe, and even the Americas.

The slave trade and slavery deeply disrupted the continent, yet the African diaspora not only survived this dehumanization but significantly influenced the world through the creation of new cultures, ideas, and ways of life.

Decades after its completion in 1999, despite the publication of abridged versions in several languages, the GHA paradoxically remained little known to Africans. It was scarcely available in libraries, rarely used in African schools or universities. African states that had supported the project at UNESCO failed to integrate it into national curricula. Worse, they continued teaching a nationalist view of history, overemphasizing colonial partition and reducing their past to encounters with Europeans.

Given this situation, one can legitimately ask why the teaching of African history remains Eurocentric over 65 years after independence. Could it be because the Pan-African and transnational perspective adopted by the GHA challenged the construction of narrow nation-states or neocolonial arrangements?

At a time when Africa is in search of its sovereignty and aims to project itself long-term through the African Union’s Agenda 2063 (The Africa We Want), this question is more relevant than ever. It calls for a critical examination of African states’ willingness to open curricula to an African and Pan-African perspective on history.

To encourage African countries to take this step and facilitate the pedagogical use of the GHA, we launched the second phase of the project in 2009, which I had the honor to initiate and coordinate until 2019. To accompany the modernization of historical education in African schools and universities, we deemed it useful to draft three new volumes of the GHA, updating the collection, reviewing the latest research on the global African presence, and analysing the new challenges facing Africa and its diasporas.

The second phase faced equally significant challenges:

Pedagogical challenge: Develop shared content based on the GHA, incorporating recent historical research. Prepared by multidisciplinary teams from different African countries, these contents had to be adaptable to diverse national curricula in countries with different education systems.

Political challenge: Secure validation from African governments for shared content offering a continental and Pan-African view of history, challenging nationalist perspectives.

Scientific challenge: Identify African scholars conducting research free from Eurocentric narratives, highlighting endogenous knowledge, experiences, and cultural resources developed by African peoples throughout history.

Today, Africans and Afro-descendants, especially policymakers, have access to a corpus of knowledge and pedagogical materials allowing them to reclaim sovereignty over the discourse on their history and contributions to human civilization. There are no longer excuses for delaying the use of these resources in education, communication, multimedia content, or AI databases.

The three new volumes of the GHA meet the aspirations of new generations of Africans and Afro-descendants striving for the continent’s sovereignty and dreaming of 21st-century Pan-Africanism. These volumes will be freely available, like the others, on UNESCO’s website.

AFROSPECTIVES contributes to global African initiatives promoting endogenous knowledge, ensuring the GHA does not return to obscurity, and that this knowledge forms a foundation for repositioning Africa in a rapidly changing world.

Ali Moussa Iye

Co-Fondateur d'Afrospectives | Anthropologue Politique

___________________________________________________________________________

The new Volumes IX, X, and XI of the GHA are organized around the key concept of “Global Africa,” integrating the history of Africans worldwide from the origins to the present.

Volume IX, “The General History of Africa Revisited,” directed by Augustin F. C. Holl, updates Volumes I-VIII (published 1981–1993), incorporates nearly 40 years of research and offering a new chronological reading of human history without dichotomies: Initial History, Ancient History, Modern History, and Contemporary History.

Volume X, “Africa and its Diasporas,” directed by Vanicleia Silva-Santos, focuses on the history of African diasporas globally. This volume compiles research on African diasporas in the Atlantic, Americas, Indian Ocean, Asia, and Southern Seas, especially Australia.

Volume XI, “Global Africa Today,” directed by Hilary Beckles, examines contemporary challenges and opportunities for Africa and its diasporas from a “Global Africa” perspective. Focusing on women, youth, creativity, knowledge production, and political transformation, it offers a critical and forward-looking vision of a continent actively shaping its future and that of the world.

Comments